Post-COVID Resiliency

Center for Urban and Regional Studies, June 19, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic is causing people around the world to question how this virus will affect the many public and private systems that we all use. We hope this collection of viewpoints will elevate the visibility of creative state and local solutions to the underlying equity and resilience challenges that COVID-19 is highlighting and exacerbating. To do this we have asked experts at UNC to discuss effective and equitable responses to the pandemic on subjects ranging from low-wage hospitality work, retooling manufacturing processes, supply chain complications, housing, transportation, the environment, and food security, among others.

Meenu Tewari is an associate professor of city and regional planning at UNC-Chapel Hill. Her teaching and research focuses on economic development with a particular interest in the implications of global competition for firms, workers, public sector institutions, and local economies, as well as the prospects for upward mobility in regions that are restructuring. In this episode, she will consider what a resilient recovery of local economies might look like.

Viewpoints on Resilient & Equitable Responses to the Pandemic

Meenu Tewari: Economic Resiliency

After nearly six months of grappling with the coronavirus pandemic, the conversation worldwide is shifting towards recovery. These are still early days, and tremendous uncertainty remains about the possible duration of the pandemic, future waves of morbidity and the spread of disease. Yet, as cities cautiously open up, many are wondering what a resilient recovery of the local economy might look like?

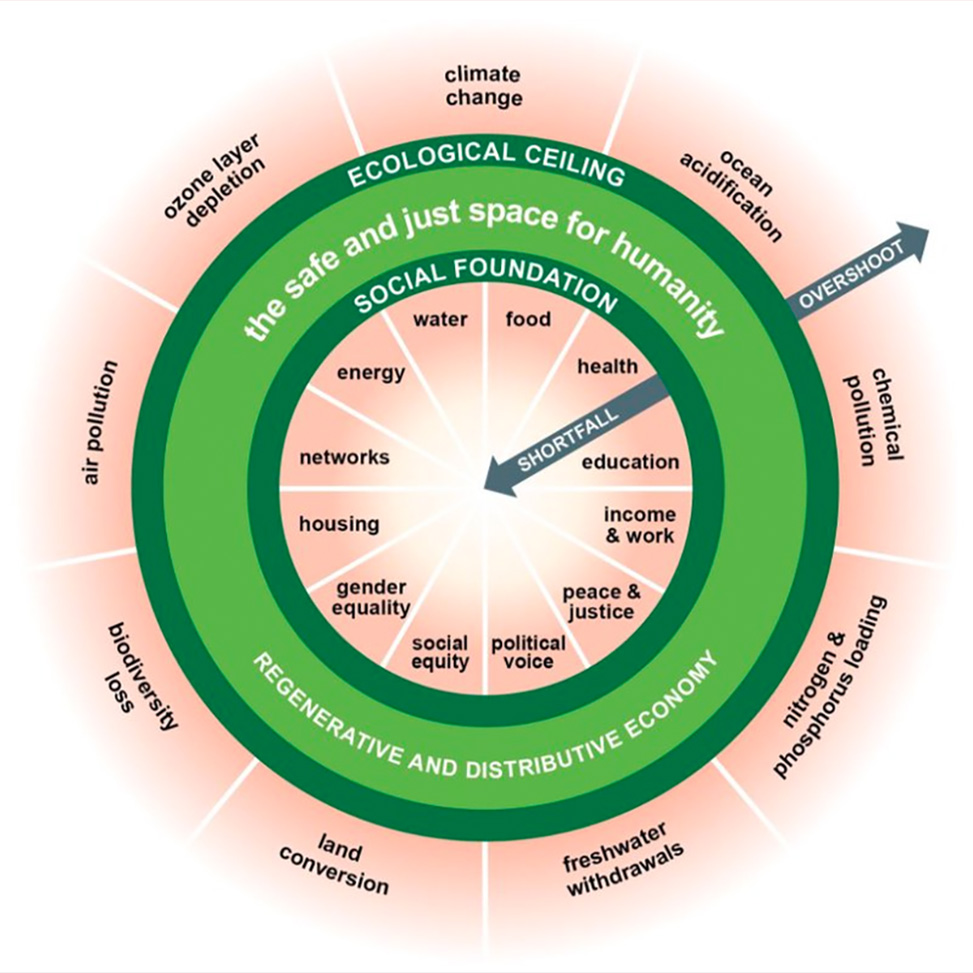

In the wake of the pandemic, the city of Amsterdam, for example, is working with Kate Raworth to adopt the “doughnut model” of development. Based on Kate’s work, outlined in her book, Doughnut Economics: 7 Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist, the city is planning its post-pandemic recovery in such a way that allows Amsterdam to thrive economically, while being in balance with the planet.

This much is clear, the pandemic has highlighted in sharp relief the deep and systemic economic and social inequities that plague our cities.

A resilient recovery, therefore, cannot be about a return to status quo. We have an opportunity to seize the moment and build a more just and transformative economic future, one that is robust, locally rooted and inclusive; one that is good for human lives and for nature.

I will make three points to illustrate this position.

First, as we all know, economic activity has shrunk worldwide, and global supply chains in most sectors have been disrupted. But the effects of these disruptions have been borne differentially by different groups and sectors.

The measures taken to slow the spread of disease – such as lockdowns and shelter in place policies – have paralyzed economic activities across countries undermining incomes, employment and well being. And we read about this in the papers everyday.

But firms and workers in some sectors have borne the brunt of this economic collapse harder than others: Studies show that the construction, tourism, transportation, hospitality, personal services, food services, restaurants, retail trades and non-essential manufacturing have all been hit especially hard.

A small business survey conducted by the Census Bureau in early May, found that about 84 percent of the businesses in the accommodation, hospitality and food service industries reported strong negative impact of COVID-19 measures, as did 72 percent of those in the education and social sectors, relative to 45 percent overall. Many among these sectors are small businesses, temporary or part-time workers, immigrants and people of color. They lack adequate safety nets in the best of times and now find themselves out of work and facing an uncertain future. Across the U.S., as we all know, jobless claims had already passed 40 million as of late May.

Indeed, a prolonged pandemic would only worsen the economic situation, magnify uncertainty and almost certainly trigger a global recession. This could further reverse some of the hard won equity goals of recent years.

- For example, the World Food Program estimates that global hunger will double this year, from 130 million to over 300 million, Chotiner 2020. Not because food supplies do not exist, but because supply chains have ground to a halt and the pandemic has exposed the fragility of food security that relies on a corporate, globalized food supply system. Indeed, many fear that a manmade famine may well follow the pandemic in many parts of the world.

- Likewise, a U.N. study projects that an additional 500 million people, or eight percent of the earth’s population will likely be pushed back into poverty due to the pandemic, UN/Wider study, cf. Nick Turse, May 2020.

- And as if this is not enough, all of this has exacerbated, in many places, the already stressed conditions over food and water access caused by climate change.

In light of these pressures, what have governments done so far? Mitigation measures have basically been of three kinds.

- First, in the formal sector, the most widespread measure has been for governments to offer income and wage supports. This has taken two forms: the traditional channel of providing laid off workers with unemployment benefits, as in the U.S. and U.K. And the more innovative form of protecting employment by providing wage subsidies to employers who retain their workers and continue to pay them full salaries, as in Holland. This latter form of support is not only cheaper than paying unemployment benefits to laid off workers, but also protects jobs.

- Second, governments have tried to provide some income supports to households and small businesses – through credit guarantees, subsidized lines of credit, deferment of taxes and loan repayments, moratoria on evictions and small amounts of welfare support to qualifying households – such as through checks in the mail, or money in bank accounts.

- Third, governments have taken measures to support the frontline segments of the health care and food system. These frontline workers, though they have jobs, have also been amongst the most exposed to the risks of disease, and many have struggled to get adequate protections and proper PPE equipment.

In other words, governments have so far mainly used their fiscal space to try to mitigate immediate economic distress, but with mixed results, and in ways that almost always require documentation and the availability of bank accounts.

But this is not enough.

For example, when you are undocumented or depend on daily work to earn a wage to feed your family, how can you benefit from the elaborate income and wage supports when they have no papers or bank accounts?

What about places or sectors where most of the workforce is self-employed, or in the informal sector, part time, or composed of migrant labor, or undocumented workers. These workers and businesses are especially vulnerable, as they are not “on the books” or registered and so are hard to count and even harder to track down. How does one support them?

Policy makers around the world have struggled with this dilemma.

This was vividly highlighted by the harrowing migrant crisis that India faced in the midst of the pandemic, where millions of informal migrant workers, left without a lifeline in cities, decided to walk hundreds of miles to their villages and hometowns – on foot, in the searing heat, without, food, water, rest or resources.

This is a glaring example of the tragedy that can unfold when countries do not or are unable to plan for their invisible workforce – a workforce that is central to building our cities and roads and running our factories, and sanitation systems – but one that has been treated as peripheral, transient, hyphenated and made up of incomplete citizens.

The same can be said of the plight of undocumented migrants in the U.S. and other countries. They are needed on the farms and factory floors, but are seen as a burden, a cost and a liability in every other way.

Even when responses to the pandemic were celebrated as successes, the benefits were unevenly distributed. For instance, when education and routine healthcare quickly pivoted online after the pandemic first broke, the quick response was seen as an achievement. However not all benefited. Those with no access to reliable internet connections, smart phones or computers, gained little.

According to a recent report, a third of school going children in rural areas were left out of the transition to remote schooling. And, even when children had access to the internet, many did not have the space in their homes or the quiet needed to focus on learning. Some had to care for sick family members or themselves became sick. Likewise, midday meals and other in-kind supports to poor students did not translate well, if at all when schools closed down.

Similarly, when we were asked to stay home. How do you do that if you have no home to begin with? When we were asked to stay six feet apart to stay safe. How do you do that when the neighborhood you live in is a dense informal settlement?

My second point, therefore, is that the pandemic may deepen racial, spatial and class divides unless cities directly address the fault lines of systemic inequality and vulnerability that are out in the open now, as we plan our recoveries.

Third, what, then, might the long and short arc of economic resiliency in our cities and towns look like?

At the outset it is critical to recognize, I believe, that our cities and communities are as vulnerable – or secure – as the weakest links in the chain. Strengthening the most vulnerable in our communities is a core part of a resilient and enduring recovery.

I am therefore arguing that this calls for a new imaginary of what I’m calling a “connected and embedded regionalism” built on mutualities between different local economies.

It is a regionalism that moves past urban and rural binaries, and sees growth as not only city-centered, but one that creates bridging spaces that are more decentralized, distributed, and capable of both connection and exchange, supported by localized and regional value chains.

Such a regionalism would help communities grow in place by connecting them creatively as parts of a larger regional ecology of innovation.

This connected regionalism calls for rethinking infrastructures and job creation.

Can job-creation be de-centered? Instead of straining urban infrastructures and deepening diseconomies of agglomeration in our metros, can connected towns and rural regions become new engines of job growth?

Can these jobs be locally rooted in ways that go beyond simply establishing new green-field Special Economic Zones, or recruiting large plants looking for low wage labor? Can work be made meaningful?

Meaningful work in my view has two elements – one restoring the dignity of work by ensuring better working conditions, living wages and safer work environments on the shop-floor. Evidence shows that these improvements boost productivity and are good for workers as well as firms. As the pandemic has shown, when shop-floors are safe, the economy is safe.

The other is improving living conditions of the poorest workers and the quality of life in the places where they live. Improving living conditions can not only boost public health, as the pandemic has shown, but also improve productivity, while creating the basis for a more livable and just society.

Related to the idea of decent work is the idea of universal basic Income. It is a debate that has had few takers so far, but the pandemic has pointed out that the time to consider moving toward a universal basic income program has finally arrived.

The infrastructures supporting this new regionalism would be those that secure lives, livelihoods, and nature. They would be good for the economy and for climate.

Ranging from more localized power systems, safe water, water harvesting, ground water recharge, sanitation and service infrastructures, these reimagined infrastructures could, both, create jobs and improve quality of life, while mitigating climate risks.

In as early as 2009, a town council member of the city of Carrboro in North Carolina had said to me that for local economies to become sustainable in the face of a changing climate they need certain self-sufficiencies and some key public goods to support that process. She named food security, water security, basic or distributed energy systems, and waste management as essential for localities and regional economies to have control over, if they have to be resilient and self-reliant. Besides this, they need to ensure healthcare and basic education.

The pandemic has shown that a resilient recovery will require one more piece: smart and equitable connectivity.

This again has two elements – the first is broadband. And we need to see broadband as a public good. Internet connectivity has been central to our ability to cope with the current crisis. Besides, it has the potential in the future to serve as an enabler of a truly connected knowledge and innovation economy that bridges digital divides, creates good jobs and fosters regional dynamism.

The towns of Wilson and Holly Springs and communities in Western North Carolina show how a variety of public broadband systems can be successfully provided by cities that are either too small or due to other market failures, have been left out by large private providers, Brian Godfrey, UNC 2020.

The second element is spatial connectivity. The pandemic has revealed that when congestion and traffic are sufficiently reduced, nature heals. The skies become blue, the air cleaner and the birds return. In this new regionalism, can we think of novel systems of mobility, connectivity and logistics that can help preserve such outcomes post-pandemic?

My final point is that these ideas are far from being utopian. Some cities are embracing just such a conception of development that can produce equitable and vibrant economies, ensure good basic standards of living and foster climate security.

In the wake of the pandemic, the city of Amsterdam, for example, is working with Kate Raworth to adopt the “doughnut model” of development. Based on Kate’s work, outlined in her book, Doughnut Economics: 7 Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist, the city is planning its post-pandemic recovery in such a way that allows Amsterdam to thrive economically, while being in balance with the planet.

The inner ring of the doughnut has all the minimum basic needs required for a decent quality of life: ranging from “food and clean water to a certain level of housing, sanitation, energy, education, healthcare, gender equality, basic incomes and political voice,” Raworth, Daniel Boffey, April 8, 2020. The outer ring provides the limits of resource use allowed by the city’s latest climate models. These ideas are being put in place even as we speak.

To conclude then, economic resiliency in the face of the pandemic represents a transformative possibility and a promise. It means not returning to business as usual, but reimagining a different, more equitable, creative and sustainable economic future for all.

Associate Professor Meenu Tewari

In her talk, Professor Tewari describes the "doughnut model" of development.